The New Vanguard

Photography by Sarah Tuck.

Female chefs are ruling New Zealand’s food scene. We meet some of the brightest young women in kitchens today.

Georgia van Prehn - Owner and head chef at Alta, Auckland

When I meet Georgia van Prehn at restaurant Alta, she walks me around the garden. There are lettuces, basil, tomatoes and oregano, growing in planters around the sun-soaked courtyard. Alta, a small restaurant on one of Auckland’s hippest stretches, serves elegant food celebrating seasonal produce. It’s always been a dream to grow some of that produce out back, making it truly as fresh and local as you can get.

It’s been a long journey for Georgia to open her own restaurant, taking over the space at 366 Karangahape Road formerly occupied by natural wine bar Clay, but she always knew she wanted to work in food. The 31-year-old says she had been cooking dinner at home – and loving it – since the age of 10.

She started in hospitality at the age of 14, working front of house. “I loved the fast pace of it and that feeling of looking after someone,” she says. She would continue working part-time during high school, eventually entering the kitchen and realising it was the only place she wanted to be, before leaving New Zealand for Melbourne at the age of 18.

Chef Georgia van Prehn in her restaurant, Alta.

Heading to Melbourne was about experiencing life outside of New Zealand, says Georgia, who knew hardly anyone when she moved. But it was also about developing her skills in a dining scene bigger than our own.

She worked at several restaurants cooking what she calls “modern Australian food” – the sort of casual fine dining Melbourne was so known for at the time, and which has subsequently caught on in New Zealand. Host Dining, now shuttered, was the most notable of these. Georgia spent two and a half years working under chefs Florian Ribul and Rory Kennedy learning “absolute heaps”. “I was pretty green at the time and they were really patient and really took me under their wing,” she says. “Rory definitely influenced the kind of food I like to cook now and taught me a lot.”

From Melbourne, Georgia moved to the UK to stage at zero-waste restaurant Silo (then located in Brighton, now in East London). “I had eaten there a year previously and loved the simplicity of the food and the use of all parts of the animal and vegetable,” she says. Her time at Silo taught her plenty about getting creative with food that would normally be considered waste – an approach she still uses in her cooking today.

After returning to New Zealand in March 2019, Georgia took on the head chef role at Scotch Wine Bar in Blenheim, before the opportunity arose to open her own space. Dan Gillett, Georgia’s boss at Scotch Wine Bar, owned Clay in Auckland and offered her the space. “I really wanted to open my own restaurant because I wanted a challenge. I’ve never really been a ‘life over work’ sort of person,” says Georgia. “I also wanted to have creative freedom over everything – not just the food, but the music, the vibe, the drink list. So having the chance to open Alta was a real opportunity.” The 22-seat space, which preserves Clay’s gorgeous tile-laid floor and open kitchen, opened its doors last year.

Opening a restaurant – particularly in the middle of a pandemic – is no easy feat, but Georgia counts herself lucky that Alta’s space was already fitted out. “A lot of people have to start from scratch and organise everything from putting in three-phase power to getting ventilation in,” she says. “I was really just tweaking it to what I wanted to be. Although of course things go wrong and you’re driving to Bunnings seven times a day because you forgot certain things!”

The excitement of opening Alta has more than made up for the long hours of its first few months. As someone who has always loved throwing dinner parties, Georgia has enjoyed creating a small, set menu only restaurant with an open kitchen. “I wanted to curate the whole experience, planning the menu, the drinks, the music,” she says. “Running Alta is like being able to throw a dinner party every night of the week. The space makes me feel like I’m a part of it as well, because I can see and hear the dining room.” The draw of a set menu is simply to offer guests more, she says – making dinner a whole experience, rather than just getting something to eat. And offering guests more is really at the heart of Alta; a distillation of Georgia’s hospitality philosophy. “Looking after someone and making their night special for them is why I do it. It’s the most rewarding feeling when you go to sleep at night,” she says.

An Alta dish of thinly sliced beetroot wrapped around smoked yoghurt and sunflower seeds, with a beetroot and whey reduction.

The food itself is something to marvel at, resisting easy labels: think octopus noodles with beef fat, orange marmalade and silverbeet, or sunflower seed parfait with apricot and rosemary. “I find it really hard to describe the food I cook,” says Georgia. “I don’t cook a cuisine like Italian or Japanese or French, and I’m not even sure you’d call it modern New Zealand food. I just cook what I feel like eating.”

The menu changes often, with Georgia tending to plan the week’s dishes on a Monday, based on what produce is available and best. “I’m not really a ‘plan months in advance’ person, I get bored too quickly,” she says. “Cooking is very much intuitive for me. I guess I would say I cook seasonally, or I would probably call it responsively – depending on what I think the yummest things I could make for the week are.” Overall, she says, she’s a fan of using every part of an ingredient – including those she’s grown herself – and likes to ferment things.

She’s excited to be part of a booming hospitality scene, despite the Covid-related challenges of the past two years. “I think the New Zealand hospo scene has gotten really, really good and it stacks up pretty well to a lot of places overseas,” she says. “When I grew up, going out for dinner was not an experience, it was a necessity. It was fish and chips on a Friday night. It wasn’t anything special. But it’s now becoming a huge part of our culture, which is amazing. I think it’s finally being taken seriously as a profession.”

With its thoughtful set menus, beautiful space and intimate vibe, Alta certainly offers a special experience for diners – a feat testament to the skills and stylishness of Georgia herself. She’s certainly one to watch.

Maria Schosser - Head chef at Depot, Auckland

When chef Maria Schosser emerges from the kitchen at Depot to meet me in the midst of a humming lunch service, she immediately offers me something to eat. “Lunch?” she presses. “A coffee? A drink?” It’s the kind of hospitality, I learn over the course of our interview, that’s characteristic of her, and also of Depot: warm, generous and unfussy.

Maria is just 25 years old but runs a busy kitchen of 13 chefs at one of Auckland’s best-known and most highly awarded restaurants. So, how did she get here?

Depot’s 25-year-old head chef, Maria Schosser.

In some ways, of the four chefs profiled here, she’s had the most traditional path towards a food career. She and her siblings were encouraged to cook at home “from a super young age”, she says, and she always enjoyed it. At school, she took Food Technology as a subject, and admits it was one of the only classes she attended all the time in her final year. One of her teachers encouraged her to pursue cooking further – so she began a Diploma in Culinary Arts at AUT, straight after finishing Year 13.

The two-year course provided a solid grounding in all facets of professional cooking, says Maria, involving everything from practical classes, to work in the cafés and restaurants on campus, to learning about how to cost dishes. She applied for a role at Depot as soon as she had finished her second year – although at that point, she’d never eaten at Depot. “I’d heard so much about the place, about it being busy but casual dining, and that really appealed,” she says. “But when I interviewed, I’d never actually dined here, and I didn’t even like oysters or offal or anything – those things Depot is so known for! It’s crazy looking back.”

During her five years at Depot, Maria has learnt a lot. Depot creator Al Brown has been a big influence, of course – and Maria has spent plenty of time with him, working not only in the restaurant but on private events. “I’ve really gotten to work side by side with him and learn the way his brain thinks and the way he conceptualises food,” she says. But former Depot head chef Andrew Mackle, who hired Maria and worked closely with her until late last year, was also a major mentor. “He took me through all my promotions through the kitchen,” says Maria. “Both he and Al have absolutely influenced the kind of food I like to cook and even the way I want to eat and the style of service.”

Maria’s cooking style draws on childhood memories, giving familiar favourites a twist. “I like to experiment with things I grew up eating and try to reflect them in a different way,” she explains. “At the moment, we’re working on a dessert for winter that’s going to involve a chocolate fondant cooked in the wood-fired oven, but it’s a play on the idea of a s’more, so there’s going to be a toasted marshmallow ice cream… It’s not intimidating. It’s just food that everyone feels comfortable eating.” Depot is known for exactly this kind of expertly executed, playful comfort food – think fresh snapper sliders; crispy pork hock with apple and horseradish; skillet cookies. It would seem Maria has taken to the restaurant’s ethos like a duck to water. When I ask her what makes Depot so special, though, it’s not the food she cites, but the people and their dedication. In particular, the senior team she works with at the restaurant have all been her colleagues for years, so there’s a long-standing sense of camaraderie and team spirit between them. “The food is cool and being a chef is fun, but none of it would be possible without having the right team behind you,” she says. “And it’s not even about your cheffing skillset – it’s about being personable, willing to work with a bunch of different personalities and cultural identities.”

The Tangaroa’s Treasures dish at Depot, featuring Cloudy Bay clams, mussels, crayfish bisque, seaweed butter and chorizo crumb.

She’s especially loved working with more female staff, and says she’s always been lucky that SkyCity (which owns Depot) has never let being a female chef in a professional kitchen feel uncomfortable. “I think there’s a shift happening, where slowly but surely, cheffing is moving towards being not such a male-dominated industry,” says Maria. “We’re lucky at Depot to have quite a few women in the kitchen. There are days when the whole team for a service is just girls.”

It’s not just about the people in the kitchen, either: the whole vibe of the Depot community – the friendly waitstaff, the laidback service, the chilled customers – is what makes it a place you want to be. “I’ve always found it kind of amazing that you can be having the best food at a restaurant but if the service isn’t great, it kind of pulls down your whole experience,” says Maria. “At Depot, I feel like we really nail the whole experience. I love the hum of the restaurant on a busy day, when the music’s loud, the seats are full, food’s flying out of the kitchen and you look around and everyone’s smiling… that’s just the best.”

When she started, Maria told herself she would make chef de partie at Depot, then move on – but five years on, and having been made head chef last year, she’s still enjoying every minute. “I’ve gone far beyond what I ever thought I would achieve in this one place, and I still love every day here,” she says. Happy where she is, she has no plans to hurry away – instead doing her bit to give Aucklanders one of the more memorable meals of their lives.

Katie Riley - Head chef at Annabel’s, Auckland

Katie Riley, 28, always wanted to be a chef. “It was the first thing I always said whenever anybody asked me as a kid,” she admits. It became a concrete pursuit after she and her dad were both diagnosed with coeliac disease at the same time, around 15 years ago. “We all started cooking more meals at home and that’s when it kind of solidified for me,” she says. “I started reading cookbooks and just fell in love with cooking.”

Katie got her first food job, aged 14, at a catering company. After high school, she headed to university to study food science and clinical dietetics and moved to Chicago for an internship at a culinary consulting company. “It was my first and last experience of the corporate world and I had a visceral sense of not belonging there,” she says. But after wrapping up, she found herself still in Chicago, one of the US’s biggest restaurant hubs, and decided to look for a food job.

She found a position at a hole-in-the-wall fine dining restaurant in North Chicago called Elizabeth, working for chef Iliana Regan. “She was this awesome ultra-feminist woman and self-taught chef, and she made this crazy amazing food,” says Katie. “Everything just clicked into place for me. I found my people, I found my place.”

Annabel’s head chef Katie Riley.

Elizabeth served 30 guests a night in two seatings of 14-18 courses each. The menu, which changed every two or three months, had a literary theme – and the restaurant became famous for its Game of Thrones and Star Wars tasting menus. “It sounds kitschy,” says Katie. “But it wasn’t just, here’s a star trooper-shaped loaf of bread, it was a little more obscure than that. It was fine dining food that was whimsical and fun.” It was also a feminine style of food and a female-run kitchen, Katie says, which was key because at the time, Chicago’s food scene was dominated by a very conventional type of male chef.

Katie views Iliana very much as a mentor. In particular, as a 21-year-old, she was inspired by Iliana’s staunch approach to criticism. “There were a lot of people in the fine dining space at that time who didn’t really like her, but she really took the approach of, I’m going to do what I do and I’m going to be successful because I know I’m good at it. I just thought, you are such a badass!”

After working for Iliana, Katie moved on to Hogstone’s Wood Oven, a pizza and fine dining restaurant “in the middle of nowhere”, on Orcas Island, off the coast of Washington state. “It’s the least recognisable restaurant on my résumé, but working there was incredibly impactful personally,” says Katie. The restaurant had its own farm and grew almost all its own produce: the only ingredients on the menu that didn’t come from the island itself were tomatoes and sugar.

A dish of kingfish crudo with kawakawa, smoked capsicum, fig leaf and coriander, prepared by Katie.

The chef there, Jay Blackington, was also an inspirational figure for Katie, who was still in her early 20s at the time she worked for him. Like Iliana, he was a young, self-taught chef who had come to cooking in an unconventional way – by reading an enormous library of cookbooks while he was a punk rocker and delivery cyclist in San Francisco. He also had a reverence for produce and the origins of food, an ethos that still shapes Katie’s cooking today. “He had these really strong rules about the ethics behind the food,” she says. “In the fall, we’d all wake up at 6am and go to the farm and slaughter the pig and break it down, and then pick some cabbages for service. That kind of thing.”

After a year Hogstone’s, Katie was keen to gain international experience and moved to Australia to work at famed Victoria farm-to-table restaurant Brae. The move was partly motivated by wanting to prove herself, she admits – wanting to see if she was good enough for what was then one of the best restaurants in the world. “My goal was to leave the US, go work for the best and get a name on my résumé that would take me places,” she says. Tired of being underestimated when she entered a new kitchen – particularly as a woman – she wanted to show the world what she was made of. “I just wanted to get to a point in my career where I didn’t have to walk into

a kitchen and have people roll their eyes, and then have to prove myself over the course of weeks. Working at Brae meant I could flip the script.”

It proved to be a worthwhile risk. Although Brae was an extremely intense kitchen, Katie says it shaped her cooking significantly and she has no regrets. Brae and its renowned head chef Dan Hunter are known for their dedication to organic, seasonal produce, grown on the restaurant’s own farm – and Dan’s understated celebration of produce on the plate changed the way Katie thinks about food. “At Brae, there’s an intense attachment to what’s being grown on the land and elevating the ingredient – taking it and manipulating it in a way that doesn’t obscure its natural beauty. Dan Hunter did that better than anyone I’ve ever seen,” she says. “His food is absolute poetry.”

Following her time at Brae, Katie came to New Zealand to work at Auckland fine dining restaurant Pasture – an experience she didn’t enjoy (last year, she spoke in detail to Metro about the problematic working conditions she experienced). But while working there, she began dropping by Ponsonby café/wine bar Annabel’s for a glass of something on her day off. One day, she discovered co-owner Henry Temple had a stack of her favourite cookbooks leaning on the bar. “I was like, what are these doing here? This is crazy!” she recalls. “At that point I didn’t have any friends in Auckland so I’d just come and drink a glass of skin-contact wine and read these cookbooks and relax. I knew this space was special.”

By this point, Katie was eager for a change, so when Annabel’s mentioned a part-time job was going pouring wine, things fell into place. She’s since revolutionised the offering at Annabel’s, single-handedly creating an ever-changing food menu and somehow cooking it all in a tiny space down the back.

One of the bar’s natural wines.

Because there’s no room for a full kitchen on site, Katie began by preparing a full dinner menu at home and bringing it in before service. She remembers it as a crazy arrangement – filleting snapper in her shared dorm kitchen at home, loading it into a polystyrene cooler in her campervan and schlepping it all over, only to realise she’d inevitably forgotten something.

After two months of off-site prep, Katie decided enough was enough. She now cooks a menu of delicious light meals and snacks – think ethereal fritto misto and irresistible aperitivo platters – in the back of the bar. Her equipment? A sandwich press, a single plug-in induction burner, a pot, a pan, a convection oven, a table-top Kmart deep fryer, and a small fridge she shares with the café in the morning.

“At first I thought it couldn’t be done,” she admits. “It took me a long time to realise there were certain things I would just never be able to do here, like a whole roasted fish or a steak. But after a while, I’d figured out the obstacles and it was just kind of fine.” Service at Annabel’s is “wildly inconsistent”, she admits – some nights, she’ll only make four or five plates of food; on others, everybody will want to eat. But as it’s never a full dinner service, Katie says, it’s surprisingly doable.

Making entirely her own food for the first time, she has discovered just how much her cooking is influenced by the chefs she’s worked for, all of whom put produce on a pedestal. “My goal is to take something simple and beautiful and change it in a way that’s memorable, but doesn’t obscure it,” she says, echoing the way she described Dan Hunter’s food to me. “I like really, really clean food – something inspired by nature and simple but elegant.” Her cooking, bright with lemon and heaps of fresh herbs, embodies just that.

Running her own kitchen has been a thrill. “I love the amount of ownership I have over what I do. I have total control, which is really unique for your first job writing your own menus and recipes,” she says. At Annabel’s, with its small staff and cosy space, Katie is responsible not only for sourcing and preparing all the food, but often also serving it to customers, clearing plates and washing up. If something falls flat, that’s her fault. But if the food was amazing, she can revel in the fact it was entirely her work. Having that kind of responsibility has been “deeply fulfilling”.

Overall, she couldn’t be happier: she’s a big fan of her coworkers – “they’re some of my favourite people that I know, full stop” – and being part of New Zealand’s growing hospo scene. “Pandemic aside, I really feel like hospitality here is on an upward trajectory,” she says. “There are so many people making great food and it’s pretty underestimated. I think we’re right on the edge of it exploding.”

So, what’s in the future for this bright spark? She’s not sure – but feeling optimistic. “I didn’t really expect to fall in love with New Zealand as much as I did,” she admits. “I don’t know where I’m going to be now – but I feel like wherever I end up, it’s going to be good. Obviously, I would love to open my own place someday – but right now, I’m really happy where I am and I’m taking it one day at a time.” We’re lucky to have her – and we at dish recommend a trip to Annabel’s as soon as possible.

Holly Tait - Chef at Pici, Auckland

Tucked away in St Kevin’s Arcade, Pici serves up some of Auckland’s best pasta from an absolutely tiny kitchen, two chefs standing shoulder to shoulder over the stove as orders pour in.

“It gets pretty hot in the kitchen,” laughs Holly Tait, 21, one of the restaurant’s chefs. “But it’s a bit of a dance and I love the energy of it. The buzz of service when you’re keeping up and you’re flowing well with whoever you’re working with… that’s just really fun.”

Chef Holly Tait slices focaccia for service at Pici.

Holly graduated from a kitchen hand position at Pici last year and she’s more surprised than anyone to find herself suddenly a chef. (She was charmingly bemused to be asked for this interview.) Despite years working in hospitality, she’s never quite believed in her cooking skills – and before coming to Pici, says she received little encouragement in the kitchen. “If you’d told me five years ago I was going to be a chef, I would have said, no f*cking way!” she says. “It’s been a happy accident and a lot of that is owed to everyone at Pici – just the encouragement factor and being shown what being a chef really entails. When I started here, I suddenly felt like oh, it would be super challenging and interesting to master this skill. Now I really enjoy it.”

Holly’s path to becoming a chef has been far from straightforward, and she’s taken in plenty of interesting experiences along the way. She started working in local cafés at the age of 15, mostly in the kitchen, with occasional front of house stints. Following a period at Best Ugly Bagels and a challenging job in a retirement village kitchen, she travelled around Southeast Asia for four months in her late teens. “I worked my butt off in Year 12,” she remembers. “I’d do about four days a week in the retirement village kitchen after school just to save for my trip. Looking back, I don’t know how I did it, but I think it did give me very good skills.”

After returning home, she took a break from hospitality – before a friend mentioned a job was going at Pici. “I’d actually walked past the restaurant before it opened and just had a really good feeling about it,” she says. “When my friend said they were hiring, I realised I did kind of miss the buzz of hospo so I hit them up – some tremendous divine timing.” After “the world’s loveliest job interview”, she settled into a role as kitchen hand – a job that came along just as she was starting to feel like committing herself seriously to a profession. “I was at a time in my life where I felt like okay, I don’t want to half-arse anything anymore,” she says. “I felt really grateful and content to be there and it made last summer so fun. I’d be at Pici from like 4pm sometimes till as late as 3am, when it was open late, and it was the best. And to be in the social bustle of Karangahape [Road]... it’s been a great time.”

After several months at Pici, head chef Jono Thevenard asked Holly to take on a chef role (“I was like, are you sure?!”) and she hasn’t looked back. With new responsibilities, her days have become much busier, something she’s enjoying.

The house dish at Pici, pici cacio e pepe.

A shift generally involves starting around 3pm, arriving to hand-roll the pici and prep for service, and then cooking alongside one other chef. “I alternate between working in the corner and working on the pans,” she says. “The person in the corner drops the pasta, reads all the dockets, matches everything up and sends the food, and the person on the pans makes what the other chef tells them. You’re both constantly cooking and sending out and it’s a fun little frenzy.”

Frenzy is the right word for it: despite its small size, Pici can do 160 covers in a night. “Sometimes I finish service and I’m just like, I don’t even know what just happened,” says Holly. “But in a good way! After service, we clean up, make everyone staff food, sit down and have a nosh and prep for the next day. There’s a big sense of friendship.”

She counts herself lucky to work in a restaurant, a place that exists simply to facilitate the act of people coming together to share a meal. “It’s so special, because people come in and have nice interactions and eat the most delicious kai that they wouldn’t necessarily think to make for themselves… you have a really fun time at a place that is literally intended for you to sit down, enjoy food and have a good time,” she says. But Pici is particularly special for its commitment to individuality; its acceptance of all customers, its inclusivity, its chill and supportive vibe. “I love that there’s no uniform,” says Holly. “I think it’s a very accepting homely kind of place and I just love that.”

Working at Pici has also taught her plenty about cooking, with Holly counting fellow chefs Kaz Suzuki, Marco Conigliaro and Jono as key mentors. Although all three have spent time in difficult international kitchens, they make Pici an inviting cooking environment and have shown her the ropes with patience and kindness. “These guys have worked in kitchens where they’ve had, like, kitchen equipment thrown at them – and I’ve heard that from so many chefs,” says Holly. “But it’s not been the case in my experience at Pici. What’s great about them is that they’ve had that experience but they still choose to be really encouraging and kind.”

Pici’s kitchen may be tiny, but it turns out some of the best Italian in the city.

Pici’s kitchen stands in stark contrast to some of her other experiences, where Holly says her age and gender made her often a target for patronising comments. Just before she took the job at Pici, for instance, Holly did a trial shift for a kitchen hand role in another café.

“I rocked up and I got asked twice, are you sure you really want to do this? Like this is a really hard job for a girl… are you sure you can handle it? I was like, what the f*ck? I couldn’t get it off my mind for the rest of the shift,” she says.

Still, her negative experiences weren’t enough to put her off altogether – thankfully for pasta fans across the city.

As well as cooking, Holly runs an art business, lazybones (lazybones.nz or

@lazybonesnz)on the side, painting skateboards and designing tattoos and promotional posters, including a few for food pop-ups. At the moment she’s also working on a photography zine and taking commissions. But she has no plans to move on from Pici any time soon – and hopes to do her bit for making other young hospo workers feel safe, comfortable and empowered in an ever more supportive restaurant scene.Feeling settled where she is counts for a lot, she says. “Honestly, I’m having a lot of fun. I just want to continue enjoying being present with what I’m doing, growing and learning.”

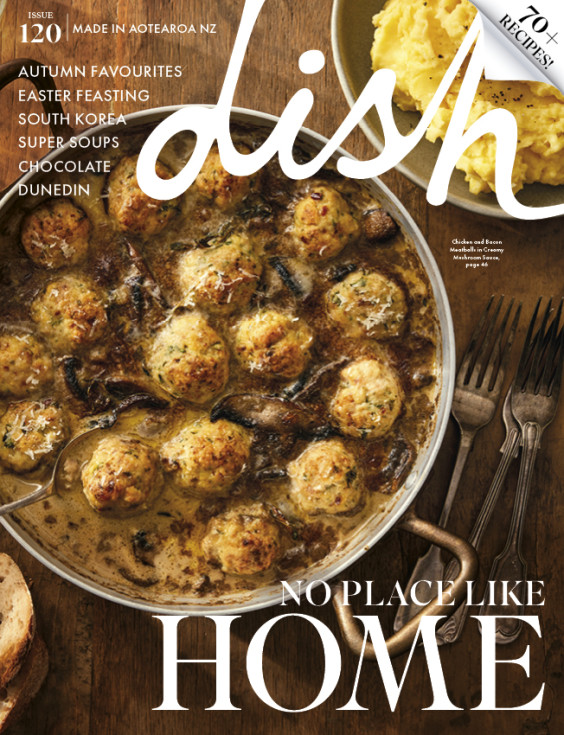

latest issue:

Issue #120

As the days become shorter, and the nights cooler, the latest issue is perfectly timed to deliver delicious autumn dishes. From recipes using fresh seasonal produce such as feijoas and apples, to spectacular soothing soups and super-quick after-work meals in our Food Fast section, we’ve got you covered. With Easter on the horizon, we feature recipes that will see you through breakfast, lunch and dinner over a leisurely weekend holiday, and whip up chocolatey baking treats sure to please. We round up delicious dinners for two and showcase a hot new Korean cookbook before heading south to Dunedin to check out all that’s new in food and dining.The latest issue of dish is on sale NOW at all good bookstores and supermarkets – don’t miss it!