A Guide To: Roasting

Photography by Aaron McLean.

Food Editor Claire Aldous has some advice when it comes to getting the perfect roast.

A roast is a Kiwi tradition, tied to our English heritage and still popular today as a hearty meal to feed the family or for a special occasion. Here are some tips to ensure your roast is the star of the show every time.

Preparation

Roasting is a method of cooking using direct heat and it’s therefore important to use the right cuts of meat: prime candidates come from the rib, back, sirloin and hindquarters of the animal and should have a marbling of fat to keep the meat moist during cooking. Whole chickens and fillets of salmon that have inherent fattiness are also ideal for roasting. Very lean cuts of meat will tend to be dry. Bone-in roasts will take longer to cook, but shrink less and will be more succulent and flavoursome.

A basic instruction, but always preheat the oven before putting anything in to cook.

When roasting vegetables try and cut them into the same sized pieces. The cooking time will vary according to their density. Softer vegetables such as zucchini and mushrooms need less time to roast than starchier produce like potatoes, carrots and parsnips.

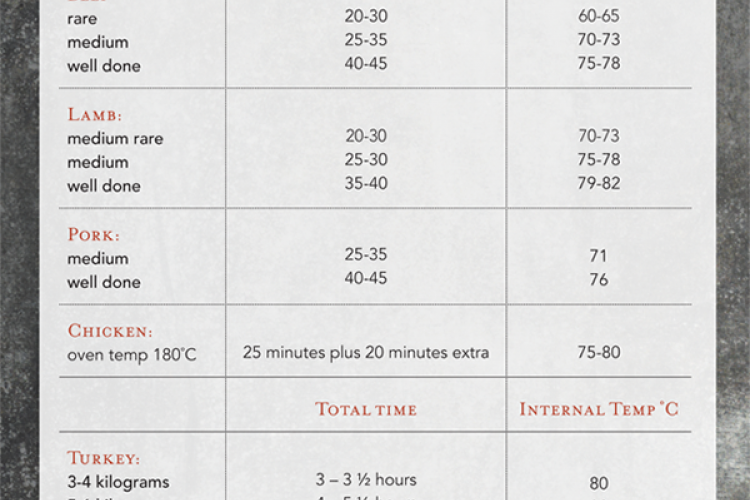

In order to calculate the required cooking time, weigh the meat and use the table below to work out the timing. You can also use a meat thermometer to determine when the meat is cooked and this will eliminate any guesswork.

Roasting can be achieved using medium and high temperatures or a combination of low and high. High (over 200˚C) is great for smaller prime cuts such as beef fillet and lamb racks. Medium (around 180˚C) is ideal for large pork roasts, legs of lamb and vegetables. Low (130˚C) is used in conjunction with high heat searing at the start until a crust or crackling forms then reducing the heat to finish cooking.

Occasionally, especially when cooking a piece of pork such as the belly with the skin on, it can have a second dish and final blast in a very hot oven to ensure the skin is well crackled.

Roasting requires little attention during cooking apart from the occasional basting, which helps keep the outside from drying out – but try not to prick or puncture the meat during cooking as juices will escape.

What to use

Roasting is generally best done uncovered in a fairly shallow pan so that air can circulate. This maintains a dry heat and allows the food to crisp and brown. If covered, the food will cook more quickly but won’t develop a nice golden colour.

For large cuts of meat, a roasting pan should be just large enough to hold the roast, no more than 7 cm deep, heavy enough not to buckle in the heat and suitable to place on the hob in order to sear the meat before roasting or to make a gravy afterwards.

For vegetables and fish use a heavy duty, shallow pan about 2 cm deep. A non-stick surface is also useful. Use a nonstick dish to roast vegetables and fish steaks Italian style with a little olive oil – they will cook fast and be well coloured.

To ensure even cooking and to prevent roasts catching and burning on the bottom, place the meat or chicken on a metal rack or trivet set in the roasting dish. If you don’t have a rack, place the meat on a bed of roughly chopped vegetables. This helps ensure you have well-flavoured pan juices to make a delicious pan gravy to accompany your roast.

Give it a rest

The final important step in ensuring perfectly cooked meat is the ‘resting’ stage. This allows the meat to relax and the juices to move back towards the centre. It helps keep the meat moist and makes carving easier.

Remove the meat from the oven and cover loosely with a piece of baking paper and then a clean tea towel to help keep the heat in. Leave for at least 10-30 minutes, depending on the size of the roast.

Good gravy

An essential component to any roast, there are two simple ways of making a good gravy.

The first is by ‘deglazing’ the pan in which you roasted the meat. Spoon off most of the fat from the pan juices and place the roasting dish on the stovetop over a medium heat. Add 1 cup of stock or wine, or 1/2 cup of both and scrape the base of the pan to release all the lovely sticky bits. Season and let this bubble up and reduce a little to give a small amount of concentrated gravy.

The second method will produce thicker gravy to serve a larger number of people. Spoon off most of the fat left in the dish in which you roasted the meat. Place the roasting dish on the stove top over a medium heat. When the remaining liquid is bubbling quickly, whisk in 2 tablespoons of plain flour to make a smooth paste. Then gradually whisk in 2 1/2 cups of good stock or 2 cups of stock and 1/2 a cup of wine and bring to the boil. Season and simmer for 10 minutes. If the gravy is too thin, keep simmering to reduce it, or if it is too thick add a little more stock. Strain the gravy into a warm serving jug.

Cook's tip

Different starches have different thickening powers and also give the finished sauce different qualities.

Plain flour will make the sauce opaque and needs to be cooked sufficiently to remove the ‘raw’ flour flavour.

The following starches need to be made into a ‘slurry’ by combining with a little cold water until smooth before they are whisked into the hot liquid. If added dry to the hot sauce, they form lumps and it becomes almost impossible to obtain a silky smooth appearance. If this happens, strain to remove any solids.

• Cornflour gives the sauce a milky appearance and the sauce will stay at the same consistency if reheated. Often used in Asian recipes.

• Potato, arrowroot and tapioca flours produce a more translucent sauce and are good for last-minute thickening. If cooled and reheated, sauces made with these flours will thin out again as extended high heat and over-stirring will nullify the thickening properties.

latest issue:

Issue #120

As the days become shorter, and the nights cooler, the latest issue is perfectly timed to deliver delicious autumn dishes. From recipes using fresh seasonal produce such as feijoas and apples, to spectacular soothing soups and super-quick after-work meals in our Food Fast section, we’ve got you covered. With Easter on the horizon, we feature recipes that will see you through breakfast, lunch and dinner over a leisurely weekend holiday, and whip up chocolatey baking treats sure to please. We round up delicious dinners for two and showcase a hot new Korean cookbook before heading south to Dunedin to check out all that’s new in food and dining.The latest issue of dish is on sale NOW at all good bookstores and supermarkets – don’t miss it!