Pantry essentials: Italian

The taste of Italy is never far away with the right ingredients on hand, as Sarah La Touche explains.

An essential section of any sound kitchen pantry is that marked Italy. We have embraced many culinary imports from far-flung corners of the world in the last few decades, but none more so than the robust and distinctive Italian flavours. Here is our pick of what to keep on hand.

Breads pane

A luxury and a staple for all Italians, the versions are many and varied. Most Italian breads are made with sourdough ferments, the long rising time creates a soft, fluffy interior and a good crust with the trademark flour left on after baking. The most popular and readily available here is ciabatta or ‘slipper bread’ so named because of the soft Tipo 1 flour used to make it. Other notable breads include campagnia, a rustic, unsalted bread often baked round or oval; and focaccia, a flat, yeasted bread made with olive oil and often stuffed with olives, onions and herbs. Grissini breadsticks are made by rolling the dough very thin and long to create a good crunch. The dough is laced with lard or olive oil, sometimes topped with poppy seeds or sesame. Panettone is the festive bread of Italy – a high, sweetened brioche bread with candied fruit and raisins scattered throughout the light buttery dough; it is eaten at Christmas and Easter traditionally.

Flour farina

Flour is graded according to its fineness in Italy. Different grades of wheat or spelt flour are used for different purposes. 00 or ‘doppio zero’ is used for making fresh pasta and cakes and ‘Tipo 0’ for making bread. These are softer flours with lower levels of gluten than durum wheat flour, which is used for making stronger dried pasta. Fresh pasta will never have the same ‘bite’ as dried pasta for this reason. ‘Integrale’ refers to wholemeal flours used for making more rustic breads. Other flours used in Italian cooking include chestnut and hazelnut, as well as buckwheat, rye and faro or spelt. (For more on flour see Dish issue #25)

Pasta

Pasta is served at every Italian table, and for grand occasions there may be two pasta courses. It is never served as an accompaniment, but stands alone as the ‘primo’ after the antipasto, and before the ‘secondo’ or main course. There are hundreds of different versions and just as many accompanying sauces, depending on the season and region. Pasta comes in myriad shapes and the sauce is essentially the garnish showcasing the pasta. Cooking pasta is an art (see pg 99 for tips) – as Gillian Riley asserts in The Oxford Companion To Italian Food: “…A well made pasta will continue to absorb the sauce as it is manipulated on the plate, changing the experience as you eat, and leaving barely

a puddle of sauce behind.”

Pasta can be fresh or dried and one is not necessarily better than the other – just different. Keep two or three different varieties of dried pasta on hand: penne, fettuccine, spaghetti or linguine will ensure quick, easy-to-prepare dishes are never

far away. Making your own fresh pasta is simple too.

Polenta

Originally the name given to porridge made from grain, we now generally think of the golden variety made from maize, but it can be made from any kind of ground grain or pulse. Rice polenta is also available here. Flavoured with herbs, or cheese like Fontina or Parmigiano, polenta tastes best when cooked for about 45 minutes and stirred continuously. (Although there are now instant 15 minute versions available.) It can be made ‘wet’ with a looser consistency, best served with slow roasted meats, stews and poultry, or poured onto a wooden board and left to set, then cut and grilled or fried in olive oil or butter. Serve this with ragouts or any saucy dishes, braised mushrooms and grilled vegetables.

Rice riso

Although better known for its pasta, Italy grows and consumes a vast amount of rice. Three different classifications dominate – ordinario or short-grained rice is best for making puddings and adding to soups. Riso semifino (medium-sized grain) is used for cooking arancini croquettes, and superfino, capable of absorbing large amounts of liquid, creates the creamy, yet firm texture required in risotto. The best varieties are Carnaroli, Vialone Nano and Arborio. Use Nano for a wetter, soupier risotto (especially good for seafood), or Carnaroli for a firmer textured version, such as cheesy, rich mushroom, vegetable risottos. Arborio falls between the two and is a good all rounder.

Anchovies acciughe

Used extensively to add backbone and flavour to many Italian dishes. They are delicious fresh, but in New Zealand we mostly use preserved anchovies either salted, in brine or in oil. The salted varieties are considered superior but those in oil can be just as good. Look for good-sized anchovies; the pinker the better. If salted, rinse them in water, milk or a mixture of water and vinegar for 15-20 minutes to soften and remove excess salt. If in oil, use them directly from the can or bottle. Whole anchovies can be rolled around olives, used in hearty antipasto or draped whole over salads and vegetable dishes. Anchovies also work stunningly well with beef, artichokes, eggs, olives, fennel, cured ham or bacon, and bitter salad greens.

Cured Meats salumi

When it comes to cured meats, Italy reigns supreme. Prosciutto Crudo and Prosciutto Crudo di Parma (considered the finer of the two) are made from pigs raised in Emilia Romagna, whose meat is salt cured and air-dried. Serve wafer thin slices in an antipasto. Bresaola is air-dried beef; enjoy it sliced thinly, drizzled with olive oil and lemon juice with sharp rocket and a shaving of Parmigiano. Pancetta is salt-cured meat from the belly of a pig (sometimes smoked) and is the Italian equivalent of cured streaky bacon. It can be rolled or pressed flat as a piece. Use it like streaky bacon: chop and cook, add to soups and stews, or slice paper-thin and serve in antipasto. Salami is the generic term for cured sausages, which are often air-dried. Traditionally made with lard and flavoured with peppercorns, fennel seeds, chilli and red wine, they vary regionally. Serve thin slices with pickled and preserved vegetables like artichokes, cornichons, olives or mushrooms in oil.

Fresh sausages

Like New Zealanders, Italians love their sausages, which are made mostly from pork as a base, with flavourings like fennel, sage or rosemary and chilli added. Sold loosely and tied with string, they are often grilled or fried, added to stews or a thick tomato ragu, and sometimes used to stuff pasta. The longer Luganega sausages resemble a Cumberland or Toulouse sausage and are sold by the yard. Salsiccia is another fresh sausage made from pork, pork fat and seasoning and sometimes partly cured. It can be grilled or crumbled to add to sauces and stews. Cotechino and Zampone are huge pre-cooked sausages, highly seasoned and often come vacuum-packed. Poach them in boiling water and serve with braised lentils or beans, or a good mashed potato.

Cheeses formaggio

The most famous is Parmigiano Reggiano (Parmesan), or its sibling, Grana Padano. Both are pressed cow’s cheeses, which become harder with more pronounced flavour as they age. Parmigiano is the stronger of the two, with a slightly moister texture. It is made in the northern region of Emilia Romagna, whereas Padano (produced on the north side of the river Po) is milder, grainier and significantly cheaper. Buy them in a good chunk and grate over pasta and soups, add to stuffings or use shaved to garnish salads and vegetables. Use the ends in soups or stocks to add extra flavour. Pecorino is a pressed ewe’s milk cheese which originated in Sardinia, but is now made all over Italy. With a mild nutty flavour, ranging to slightly piquant for the more robust versions, it is delicious served as a table cheese when young, then once aged use it like Parmigiano. Mozzarella is traditionally made from buffalo milk and is snow white with a smooth, delicate texture and appealing flavour. High demand means much of the cheese is now made from cow’s milk, but the two are quite different. Fresh Italian buffalo mozzarella is available here, but there are also some excellent local versions now, such as that from the Clevedon Valley Buffalo Company. Eat it fresh and do as little to it as you can; break it into soft, pillowy pieces over fresh tomatoes with bright basil leaves, good olive oil and freshly ground pepper. Also try it with grilled eggplant and other roasted vegetables. Ricotta is made from the whey left over from cheese making and should be bright white and fluffy with a delicate flavour. Use it to fill tortellini or ravioli, stuff quail or poussin, add to tarts, or sweeten with honey and serve with poached fruits. Mascarpone is more of a rich, buttery cream than a cheese. It is delicious for dessert making and adds richness to sauces and savoury mousses. Soften and lighten it by adding a little milk and serve instead of cream with poached fruits and sweet tarts or cakes.

Three other cheeses worth experimenting with are Fontina – a full-fat semi-soft cheese made in the Valle d’Aosta and similar to Gruyère. It melts beautifully so can be used in sauces and as a table cheese. Gorgonzola is Italy’s most famous blue cheese – a noble, full-fat, creamy cheese with a rounded piquancy – it ranges from mild and creamy to strong and sharp. It melts well into sauces for dressing pasta or gnocchi. Taleggio is a rectangular washed-rind cheese that is soft and buttery and develops an appealing tang and sweetness with age. Slice over warm polenta, add to risotto, stuff ravioli or use on a cheese board.

Herbs erbe

Basil is the herb most synonymous with Italian food – the small leafed variety has the most intense flavour and is used extensively, especially in Liguria, the home of pesto. The larger leafed and purple varieties are slightly less pungent. Basil is best used fresh and just picked, its flavour dissipates when cooked. Oregano and marjoram are best harvested in flower when they are most pungent. Oregano is used fresh in summer but is best dried; look for the highly prized Sicilian dried oregano in specialty food stores. Italian flat-leafed parsley has an intense flavour and is the prime ingredient in salsa verde, which can dress grilled meats and fish, or roasted vegetable dishes. Rosemary is best used in small amounts; the leaves can be used to perfume breads like focaccia, in sauces and braises, and for flavouring grilled meats, especially lamb and vegetables. Sage is excellent with meats, particularly veal, pork, fish, and for bean dishes, as well as pasta. Thyme is used widely too and is as effective fresh as it is dried.

Spices spezie

Italian cooking uses many spices, but some stand out. Chilli or ‘peperoncino’ is used extensively in southern Italian cooking. Either fresh or dried, Italian chilli is generally a softer heat, except in the region of Calabria where the flavours are quite fiery. Dried, flaked and mixed with dried garlic, parsley and extra virgin olive oil, it becomes the staple dish of ‘spaghetti al peperincino’ – a hearty pasta dish found in many trattoria throughout Italy. Fennel seeds are highly aromatic and used in sweet and savoury dishes, liqueurs, breads, pastries and salami to impart their distinct sweet aniseed flavour. Saffron is expensive but worth it, as only a pinch of these dried crocus plant stamens will flavour risotto, breads, fish dishes, soups and stocks. Its unique fragrance lends elegance and complexity. Look for brightly coloured stamen with a heady fragrance.

Dried Mushrooms funghi

The most famous is porcini, regarded as the best because it retains its meaty, intense flavour when dried. Look for bags that contain whole or large chunks of mushroom. Soak in warm water for around 30 minutes before use, and keep the flavoursome liquid to strain and add to sauces and stocks. Use porcini in soups and sauces, risotto, polenta or mix with button and Portobello mushrooms cooked with butter, garlic and fresh parsley. A great accompaniment to beef or game.

Capers capperi

These are not the fruit of the caper bush, as you might expect, but the bud. Inedible when raw, they are cured in vinegar, brine or salted, and the smaller the caper, the more intense the flavour. Those grown in the Sicilian Islands of Lipari or Pantelleria are considered the best (see pg 117). Soak salted capers in water for 15-20 minutes before use, and add towards the end of cooking so they retain their distinct flavour. Use in pasta sauces or with meats and fish; for dips and pastes or sprinkling over salads. Some ‘false capers’ are made from the larger bud of the nasturtium. Caper berries are the larger fruit, and are eaten pickled.

Beans fagioli

Known as ‘poor man’s meat’, beans are eaten fresh in the summer months, or dried for convenient year-round use. Beans are also readily available in cans at most supermarkets and specialty food stores. The most common varieties are borlotti, a small magenta streaked bean when raw, turning pale brown once cooked and most popular in the north of Italy. With a creamy texture and nutty flavour they work best with hearty winter dishes, and in soups with pasta.

Cannellini are a slightly larger version of the white French haricot bean. Excellent in salads, for mashing and whipping into dips because of their light, fluffy texture and delicate flavour. They feature in minestrone and as accompaniments to meats and fresh sausages such as cotechino. Serve instead of potatoes, cooked slowly with olive oil, garlic

and sage.

Bianche di Spagna, the largest of the beans, are similar to butter beans and wonderful with offal and pork, fennel sausages, braised meats or poultry. With a delicious bite, creamy texture and a mild flavour, they are lovely in salads and soups too.

Dried fava or broad beans sold in their skins, or skinless, make delicious purées or stews to braise with pork belly and hot Italian sausage. Serve them as a plain mash cooked with golden olive oil, garlic and chilli and sautéed greens like cavolo nero or savoy cabbage on

the side.

All dried beans must be soaked overnight and cooked in unsalted water for at least one hour; they become smaller and harder as they dry so the older the bean, the longer the cooking time. Where possible, buy dried beans from the previous season’s harvest that haven’t been heat-treated.

Tomatoes pomodori

No self-respecting Italian cook would be caught short without tomatoes in their cupboard and there are now many good quality versions of canned tomatoes available.

Always choose a good Italian brand of plum tomatoes – use a polpa di pomodori or crushed pulp with lots of texture, or passata, a finer sieved version without pips. (We call this tomato purée.) Ideally, spend a lazy Sunday cooking and bottling your own versions of these classic store cupboard staples to use through winter.

With a can or two of good tomatoes in your cupboard, a little garlic, some olive oil and a packet of dried pasta you can have a hearty meal on the table in 20 minutes.

Sun-dried tomatoes can be used in sauces, ragouts, dips and stuffings for pasta or meat, or serve in antipasto. Tomato paste adds a snap of concentrated flavour to a dish – a little goes a long way so you only need a teaspoon or two. Look for good Italian brands without added sugar.

Pine nuts pignoli

These are harvested from the large pine cones of the stone pine, which grows in the Mediterranean region, and are used extensively in many southern Italian dishes, both sweet and savoury. Pine nuts contain high amounts of oil so eat them as fresh as possible as they can become rancid quickly. Buy in small quantities from a store with a reliable source and store in the freezer.

Truffles tartufi

This revered fungus grows underground and three varieties dominate in Italy: the black or winter truffle, tartufi nero; the white truffle or tartufi bianchi and the scorzone or summer truffle, which is similar to the black, but less perfumed and cheaper.

Fresh truffles are available in New Zealand (sometimes at farmers’ markets after the season starts here in mid-May) but the industry is still in its infancy. Eat fresh truffle raw, store with eggs to perfume them before scrambling, or shave onto a simple dish of egg noodles folded through a golden, buttery sauce.

Truffle oil is a simple way of enjoying truffle year-round and a more economic way of perfuming a good risotto, mushroom or pasta dish, or drizzle it over silky smooth potato purée. Look for a quality extra virgin olive oil flavoured with a piece of truffle – beware cheap imitations where the oil is scented with synthetic truffle fragrance.

Olive Oil olio di oliva

One of, if not the most important ingredient in Italian cooking, olive oil is used in a huge range of dishes. Oils vary enormously from region to region and can be single estate or blended and flavours vary too: fruity or peppery, subtle or bold. Extra virgin olive oil is made from the fresh juice of the olive, which is pressed and the resulting liquid separated into oil and water. Invest in a good quality Italian extra virgin olive oil to use as a condiment for drizzling over bruschetta, salads or antipasto, and adding to hot dishes just before serving for a last minute rush of flavour. It can also be used in baking breads, cakes and sweetmeats. A less expensive

extra virgin olive oil can be used for cooking.

Balsamic Vinegar aceto balsamico

A rich wine vinegar originating from Modena in Italy, which becomes intensely concentrated with age. The most prized is the Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena (see pg 30 for more). It is worth investing in a well-matured, five year old balsamic to use sparingly when dressing salads, drizzling over grilled meats, poultry and fish, or strawberries. The lesser quality balsamics of one year can be used for marinating, but beware cheap imitations that are just normal vinegar with burnt caramel syrup added. White Balsamic Condiment can be used similarly, but is very sweet with added sugar.

Wine and liqueurs for cooking

Many regional dishes are cooked with a glass or two of the local wine. It adds depth and concentration of flavour and is added to stews and slow-cooked braises, and used to marinate tougher cuts of meat and game.

It is also added at the end of cooking to deglaze the pan in which the meat has been cooking, and finish a sauce. Aperitifs like Martini can be used or a simple red or white of the region. Liqueurs like Sambuca, Frangelico or Amaretto flavour desserts like tiramisu, biscuits and pastries.

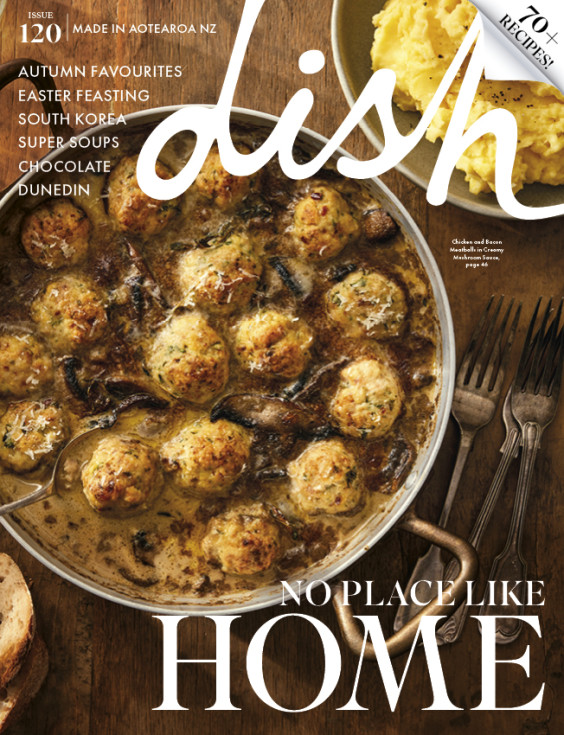

latest issue:

Issue #120

As the days become shorter, and the nights cooler, the latest issue is perfectly timed to deliver delicious autumn dishes. From recipes using fresh seasonal produce such as feijoas and apples, to spectacular soothing soups and super-quick after-work meals in our Food Fast section, we’ve got you covered. With Easter on the horizon, we feature recipes that will see you through breakfast, lunch and dinner over a leisurely weekend holiday, and whip up chocolatey baking treats sure to please. We round up delicious dinners for two and showcase a hot new Korean cookbook before heading south to Dunedin to check out all that’s new in food and dining.The latest issue of dish is on sale NOW at all good bookstores and supermarkets – don’t miss it!