A guide to: raw milk cheeses

Photography by Manja Wachsmuch.

After years on the banned list, raw milk cheeses are finding a following here. Sarah La Touche highlights some of the best...

In the world of cheese where aroma, flavour and texture are paramount, raw milk cheeses are regarded with a special kind of fervour. Their complexity and characteristics are believed to be unique, setting them apart from cheeses made with milk that has been pasteurized.

Up until fairly recently, raw milk cheeses were out of reach for New Zealand cheese fans as food safety concerns around products made with unpasteurized (or ‘raw’) milk meant regulations prevented their importation and sale.

Some Swiss hard cheeses made from raw milk such as Gruyère, have been allowed into New Zealand since 2002, with Italy’s Parmigiano Reggiano and French Roquefort following in 2007, but softer cheeses were treated with more caution. Then in October 2009 new standards meant a wider range of cheeses could finally be imported and also opened the door to local cheesemakers looking to make their own raw milk cheeses.

The new standards around the importation of unpasteurized cheeses into New Zealand are stringent, requiring clear labelling, certification for MAF clearance and strict criteria to which importers must adhere. The countries from which unpasteurized cheeses can be imported are also heavily regulated; and producers have their cheeses laboratory tested prior to export.

Similarly tight regulations will apply to the production of raw milk cheeses within New Zealand. While there aren’t any local raw milk cheeses available for sale currently, MAF says it has been working closely with four cheesemakers in establishing protocols around the process, which is in its early stages.

For many, unpasteurized cheeses are a bit of a mystery and the debate over their safety only adds to the confusion. Raw milk is milk gathered from cows, ewes, goats and buffalo, which is not heat-treated before being consumed, either as milk or milk products like cheese.

When milk is pasteurized it is heated to between 63-89° Celsius for 1 second to 30 minutes depending on the process, before it is cooled immediately. The heat destroys pathogens that cause harm and spoilage, as well as harmful bacteria that can cause diseases such as listeria, salmonella or tuberculosis – of particular threat to pregnant women, the immune compromised, young children, the frail and elderly. (It is worth noting that soft rind-washed cheeses like Camembert and Brie, and blue cheeses pasteurized or not, are particularly risky for these groups.)

However, pasteurization also destroys the milk’s good bacteria, which help a cheese develop taste, aroma and character, as well as protecting it from harmful bacteria and extending its life. While pasteurization is valid for industrial cheesemaking where milk is gathered on mass and stored over time (two elements that increase the risk of contamination), it is less relevant for small artisan cheesemakers who can control hygiene and other variables more stringently. There is also an argument that altering the milk’s natural qualities through a process such as pasteurization makes it more susceptible to infection.

Raw milk cheeses (or lait-cru as the French call them) are mostly made seasonally by local producers in smallholdings. Their animals don’t produce milk all year round and each particular environment contains its own set of natural mould spores and friendly bacteria that help create the right balance of acidity in a cheese; they add subtlety of flavour, reduce harsh notes or blandness and create textures that melt in the mouth.

When you buy a Sainte-Maure de Touraine from the Loire Valley in France it will have all the characteristics of that particular variety of goat’s cheese made in that region, and yet each cheese will also have its own personality according to where the goats have grazed, the season and the weather.

Ageing is also a crucial step in the life of a cheese, as its texture, flavour and aroma develop. Some raw milk cheeses become more intense while others soften, becoming nuttier, or peak with intensity before tailing off with more subtle notes.

In France, the aging process is known as affinage and takes place under controlled conditions that manipulate elements such as temperature and humidity. Specialist affineurs know how to bring a cheese to ‘ripeness’ for optimum enjoyment. Some, like a good Brie de Meaux, may take only a matter of weeks, while a fine Parmigiano Reggiano could age two years before reaching its peak.

Because raw milk cheeses are often seasonal, not all varieties are stocked year round. Listed on the following pages are some now available in New Zealand through a small selection of importers. When buying, make sure you ask when the cheese will be at its optimum for eating, and how best to store it.

RAW COW’S MILK

Brie de Meaux - a large round, flattish, soft cheese with a bloomy, white rind. Its creamy texture delivers a superb combination of hazelnut and yeasty flavours with a delicious hint of mushroom. Eat on its own or add slices of green apple, some walnuts and a glass of Champagne. Affinage usually takes around 8 weeks. When buying, at least half the thickness of the cheese should be ripe, the texture even and straw coloured, with a delicate though distinct aroma of mould.

Beaufort AOC* – a pressed and ‘cooked’ hard cheese from the region of Savoie in the French Alps with a dense, whitish pâte (interior) and golden rind. An average Beaufort weighs around 40 kilograms and is cut into wedges for sale. Ageing takes between 4 months to a year. A good Beaufort will have a slightly sticky crust and a concave surface formed by the cercle de Beaufort – a band placed around the cheese during its first pressing. Initially mildly fruity and sweet, these flavours deepen with age. Look for notes of honey, butter and herbaceous aromas. Slice thinly for maximum flavour, grate into sauces or over grilled vegetables. At its best between mid-November and mid-April.

Camembert de Normandie AOC – synonymous with good French cheese and enjoyed year round, this Camembert has a rich creamy texture, bloomy beige/white rind and soft yellow interior. The degree of maturity denotes its flavour with nutty, salty subtleness and a slight fragrance of mould. The cheese should be completely intact and give slightly to finger pressure. It can be eaten moitiémoitié, meaning ‘half and half’, so the heart of the cheese is still white but not yet creamy with the outer portion nicely soft and gooey. Camembert is ripened to a minimum of 21 days.

Livarot Graindorge AOC – Normandy’s second most famous cheese after Camembert. Its beautiful pinky/gold sticky crust is encircled with five bands of rush raffia, which prevent the cheese

collapsing during aging. Reminiscent of an officer’s military stripes, these bands have earned it the nickname ‘The Colonel’. A strong smelling cheese with a full and spicy flavour. Make sure the Livarot you choose is very ripe – the interior should be firm (unlike a Camembert) but moist. Best from mid-April to mid-November.

Morbier au lait cru – a supple, sweet cheese from the Franche-Comté. It has a fresh creamy texture with an appealing, slightly acidic finish and firm rind. The pale ivory interior is distinguishable by a vein of bluish vegetable extract (ash used to be used), running across the centre. Affinage takes up to two months.

Munster AOC – with its slick and shiny brick-red rind, this pungent smelling cheese hails from Alsace. Its soft, smooth texture has the consistency of melting chocolate when ripe. Sweet and richly reminiscent of milk in flavour, it is traditionally eaten with cumin or boiled potatoes in their skins.

Parmigiano Reggiano – concentrated sweetness, salty but not overly, and distinctive. A cheese loved for its depth of flavour and crystalline graininess. Grated or shaved over pastas, soups, in sauces or salads it is the perfect flavour enhancer. In Italy it is enjoyed at the end of a meal cut into bite-sized morsels with or without a dram of aged balsamico. Matured for between 12-36 months and priced accordingly.

Reblochon de Savoie AOC – from the spectacular mountains in the Savoie, this cheese has a nutty, mild, mushroomy flavour and a soft, smooth texture. Made with the thicker, richer milk from the second milking. The firm, yellowy-orange rind often sports a natural white mould. Delicious on its own but also cooks well in sauces and tarts – especially the famous Savoie specialty tartiflette consisting of onions, potatoes, bacon and melting Reblochon.

St Nectaire AOC – one of France’s finest cheeses from the Auvergne region. Its greyish-golden rind mottled with white, yellow and red patches encases a tasty semi-hard but supple interior. The cheese is placed on rye straw for ripening and washed with brine. Ripening takes up to eight weeks before it is ready to eat. Its distinctive smell, reminiscent of damp cellars and grassiness is curiously appealing, and its sweet nuttiness is balanced by acidity, with hints of spice and walnuts.

Clockwise from back left: Swiss Emmentaler; (from top)

Swiss Raclette, Swiss Emmentaler and Swiss Gruyère;

(front) Parmigiano Reggiano.

Swiss Emmentaler – a cooked, pressed cheese famous for its holey appearance and appealing tangy nuttiness. Lactic bacteria interact with oxygen to create the characteristic ‘eyes’ during maturation. Aged from four to 12 months, one cheese can weigh from 60-100 kilograms. Perfect for grilling or grating. Traditional fondue is always made with Emmentaler and Gruyère.

Swiss Gruyère – a creamy pale cooked and pressed cheese from the fairytale village of Gruyère and its surrounds. Slightly granular with a rich nutty flavour and when aged can rival a good Comté or Beaufort. Especially good for French onion soup or melt into tarts, over potatoes or pasta.

Swiss Raclette – the ultimate winter cheese, Raclette is traditionally melted from the half round by the fire then scraped over boiled or roasted potatoes and served with cornichons and pickled onions. Nowadays modern Raclette grills make life easier. Despite its firm texture it melts beautifully with a full, milky flavour. Aged for eight weeks it’s ideal for toasted sandwiches and grilled toppings.

Tomme de Savoie – Tomme is the generic word for semi-hard cheeses made with cow, goat or ewe’s milk or a blend of these, crafted by specialist cheesemakers in the mountainous regions of France. This version sports a fawny-grey crust, often with reddish patches. The semi-hard pâte is a little like Cheddar yet not crumbly; melt-in-the-mouth when ripe with notes of earthy mushroom, caramel sweetness with a pleasing fruitiness. Great for robust sandwiches, omelettes or a good Béchamel sauce.

Vacherin Mont d ‘Or – from the border near Switzerland, this sublime cheese marks the end of the cheesemaking year and the celebration of the festive season. Wrapped in spruce wood, the scent permeating the cheese, it is sold in the wooden box in which it ripens. The washed rind is orange-red, the interior a pale cream. In fact it is so creamy it is best served with a spoon, ideal for spreading on good bread or over boiled potatoes. Only made from August to March.

RAW GOAT’S MILK

Sainte-Maure de Touraine – with a delicate grey-white mottled rind this distinctive, cylindrical shaped cheese is one of the standout goat’s cheeses from France. It is distinguished by a straw which runs through its centre (used in the cheesemaking process) and marked with its AOC seal and producer number. Slightly salty and nutty, smooth and round in the mouth with sweet walnut aromas. Best from mid-April to mid-November.

Front: Sainte-Maure de Touraine with its distinctive straw;

Moubier. Livarot Graindorge AOC with its raffia bands (on stand);

Brie de Morbier (at back).

Banon – originally from a small village near the town of Banon in Provence, Banon is made from goat or cow’s milk. At two weeks it’s bathed in eau-de-vie then wrapped in softened chestnut leaves and tied with rush twine to ripen for a further 2-3 weeks. The alcohol protects the cheese as it ripens and takes on the colour and perfume of the leaf. Some versions are rolled in dried savory. The cow’s version is available all year round, the goat from spring through to autumn.

Valençay – distinct with its charcoal/salt coat and shaped like a flat-topped pyramid. As the cheese matures a natural mould mingles with the charcoal protecting the chalky ivory-white interior. Sweet and soft, it matures to a firm, richness with distinctive nuttiness. Minimum aging is eight days with a further three weeks for an average cheese.

RAW SHEEP’S MILK

Roquefort Papillon Black Label AOC – its clean, salty, assertive flavour has made Roquefort one of the three greatest blue cheeses in the world. Look for its distinctive veins of blue-grey mould, creamy-white moist, crumbly pâte and characteristic aroma. The sweetness of the milk complements the saltiness of the cheese and tang of the mould on this melt-in-the-mouth cheese. Traditionally part of a salad with garlicky croutons, lardons and walnuts, serve it as a rich heart-stopping sauce with rare beef or pasta, with raisin bread, soft gingerbread or fruit pastes. And best of all, on its own with a glass of Sauterne or Muscat.

Top shelf from left:Valençay; Beaufort; Camembert

de Normandie (front in box); Tomme de Savoie (back

in glass dome); Reblochon. Bottom shelf front from left:

Emmentaler; Munster, Sainte-Maure de Touraine; Morbier.

On table: Brie de Meaux.

For details on regulations around unpasteurized milk products visit the New Zealand Food Safety Authority website at nzfsa.govt.nz

*AOC: this refers to Appellation d’origine contrôlée or “controlled designation of origin”. It is a certification granted to products made only within a specific geographical area.

For stockists of raw milk cheeses contact C’est Fromage, Raw Energy and Sabato

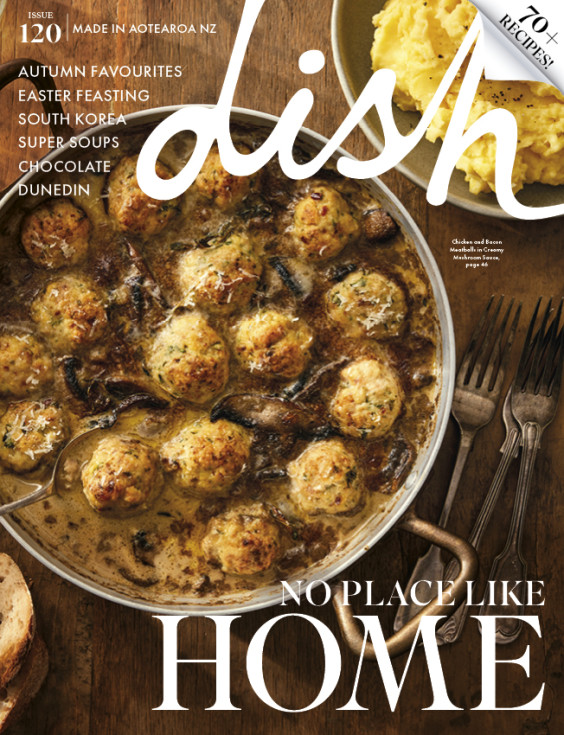

latest issue:

Issue #120

As the days become shorter, and the nights cooler, the latest issue is perfectly timed to deliver delicious autumn dishes. From recipes using fresh seasonal produce such as feijoas and apples, to spectacular soothing soups and super-quick after-work meals in our Food Fast section, we’ve got you covered. With Easter on the horizon, we feature recipes that will see you through breakfast, lunch and dinner over a leisurely weekend holiday, and whip up chocolatey baking treats sure to please. We round up delicious dinners for two and showcase a hot new Korean cookbook before heading south to Dunedin to check out all that’s new in food and dining.The latest issue of dish is on sale NOW at all good bookstores and supermarkets – don’t miss it!